Sports

How a 6-year-old marathoner ignited America’s parenting debate

Published

5 مہینے agoon

By

l955w

“Oww,” he cries. “I hurt.”

A scrape the size of a quarter throbs on his right knee, and after a bystander volunteers to retrieve a bandage, Kami Crawford squats so she’s at eye level with her son, holding his hand. “I know you didn’t want to fall,” she says. “But it happens. Remember how it hurts for a little bit and then it stops hurting? That’s what’s going to happen.”

When the Crawfords started nearly five hours ago, the early May morning was dark and cool. Now sweat plasters Rainier’s blond hair to his forehead. He tells his parents he doesn’t think he can finish the race, a Crawford family tradition he begged to take part in after years of watching his five older siblings run it. In the months leading up to the marathon, Ben, Kami and Rainier ran three times a week, in the snow, rain and heat. Rainier liked it best when they stopped at a bubble tea shop along the route. He pictured crossing the finish line and coming home with a shiny medal.

“What do you want to do, Rainier?” Ben asks now.

“I don’t know.”

Rainier grasps Kami’s right hand in his left and takes the first of several steps. Every few paces he stops to stretch. “Go away, my sore,” he says. Three miles down the road, they shuffle upon a playground, and Rainier runs off course to scramble up a climbing wall. A few minutes later, Ben tells him it’s time to go. Rainier sees his friends holding posters decorated with his name, and picks up the pace. When the trio reaches an abandoned aid table at mile 20, Rainier cries again, and Ben promises to buy two cans of Pringles after they finish.

They keep inching toward downtown Cincinnati and at mile 25, he reunites with his siblings, who had been waiting so the family could finish together. Eight hours and 35 minutes after they started, all eight Crawfords cross the mostly deserted finish line, hands linked. Katy Perry blasts over speakers as a race volunteer places medals over their heads. Rainier grips his medal tightly, beaming. Kami kisses Rainier’s forehead. Ben pulls him in for a hug.

Days later, after the Crawfords’ marathon images go viral, after an Olympic runner tweets disapprovingly about them, after “Good Morning America” interviews the family from the backyard of their home in Bellevue, Kentucky, after someone eggs one of their kids’ windows, and after Child Protective Services visits their home, Ben and Kami are left to wonder how the story of a kid doing something extraordinary has turned into a story of a kid suffering under abusive parents.

“Our story,” Ben says, “became this kind of masthead for what a lot of people are really afraid of in parenting.”

BUILT FROM RED BRICK, the Crawfords’ home rises three stories in a historic neighborhood less than 10 minutes from the Ohio-Kentucky border. It’s a lazy Saturday morning in March 2023, nearly a year after the Flying Pig Marathon. Inside, blueberry pancakes pile high on plates scattered around the dining table, a 4-by-12-foot slab of wood.

Years ago Ben looked everywhere for a table that would fit a family of eight and noticed that most of the furniture from places like Crate & Barrel and Pottery Barn came “distressed.” To him, the worn wood told an inauthentic story of hard work and creativity. He paid a friend to build one instead, and on the bottom they burned an inscription into the wood: “A place to create, write and tell stories.” The christening mark was made by placing a hot cast-iron skillet in the middle of the table, and after that, it was fair game for the kids to distress the table with whatever they could find. Ink, paint and dents now pockmark its surface.

A few feet away from the table, shoes of various sizes spill over their designated racks and scatter around the front door. On the right, coats, purses and two sets of keys hang on a wall partially painted fire-engine red. Swaths of it remain white, as if someone forgot to complete the job and let the paint drip dry. When the Crawfords moved in over a decade ago, Ben felt what he describes as a spiritual draw to splash the entryway with red. He worried at first it was ruining the house. But it set the tone — it was their home and no one else’s, and it should reflect the family living in it, which meant things would change and transform and that was OK.

To see their house is to begin to understand the Crawfords. Six years ago, Ben and Kami hiked the entirety of the 2,190-mile Appalachian Trail with their family, ages 2 to 16 at the time. Most of their kids — Dove (22), Eden (21), Seven (19), Memory (17), Filia (13), Rainier (8) — have never attended school. They believe that children often know better than adults, that it’s OK to let them say “s—,” and to ride shotgun no matter how young, that it’s more than OK to let them paint on the walls, because art is a form of self-expression and allowing their kids to express themselves freely is more important to Ben and Kami than nearly anything else. They believe that the relationship between parent and child should be more collaborative than authoritative, and that when your 6-year-old asks to run a marathon, you let him.

Most marathons have a minimum age of at least 16 years old — the Flying Pig’s is 18 — but Ben and Kami say they will continue to support Rainier as long as he wants to run, even if it means defying race policies and critics. They believe that is what good parents do, that they are fighting for the same thing many other parents are fighting for, in ways small and large: the right to parent with freedom.

After breakfast, Ben sits at the head of the dining table with his slippered feet propped up against one of the benches. He pops on the glasses that had been on the table. “Wow, that’s much better,” he says. His vision is terrible, and without his glasses, Ben admits, my face had been a blur since my arrival nearly two hours earlier. The frames are clear and stylish. His dreadlocks, streaked with gray, tumble wildly past his shoulders. A few years ago, a psychedelic experience convinced Ben to grow his dark hair long, and when he decided to style it into dreadlocks, it felt to Ben that his hair had become an outward reflection of a transformation within, of a decision he made years ago to live more authentically, even if it felt counter to cultural norms. In his mid-40s, he is giving himself permission to do the things he wanted at 18.

Ben tells me he doesn’t really care what anyone thinks of him or his family, if anyone suggests he and Kami are terrible parents for letting Rainier run in a marathon, or for letting him run the next day in the 2023 Cincinnati Heart Mini-Marathon, when temperatures are supposed to drop below 20 degrees. A few minutes ago, Ben sent Seven to pick up the race packets for the half-marathon, an event his youngest child is not officially allowed to run but will anyway.

This stuff riles him up.

“If you follow everything that you’re supposed to do as a parent you get applauded,” he says, straightening his posture as the words rush out. “If you take your kid to the doctor, if you send your kid to school, if you take your kids to McDonald’s, no one asks if these things are good for you. It doesn’t matter. I’m not saying they’re bad for you. I’m just saying if you do what’s regular, if you do what’s normal, people are like, ‘Wow, you’re a good parent.’ But if you do something that you believe is better for your kid, the amount of risk … it’s so disincentivizing. It’s scary to parent in a way that you think is best for your child.”

Later, Seven returns with race bibs for Ben, Seven and Memory. Rainier will run unregistered, which many within the running community consider to be race banditing — essentially stealing. But Ben says they would pay for Rainier if they were allowed to.

“Kids are some of the most disenfranchised people,” he says, his voice rising. “They don’t have rights that adults do. If you said a Black person isn’t allowed to participate in this race, or a woman, you’d be f—ing crucified right now — and rightfully so. But if you say a 7-year-old can’t, people are like, ‘Oh, that’s smart and responsible.'” His two oldest daughters, Dove and Eden, are running in the Los Angeles Marathon the same weekend with their friends. He wants his 7-year-old to be able to make the same choice.

“Complete discrimination,” Ben says, shaking his head.

BEN AND KAMI call each other “Babes” a lot — “Babes, can you get the coffee?” — and grew up 45 minutes away from each other in the Seattle suburbs. Kami’s dad was an army chaplain and church pastor; Ben’s dad was a missionary in Korea during the early ’70s, which is where he met Ben’s mom, who is Korean. In Washington, the Crawfords attended a Plymouth Brethren church. In high school, Ben wore Christian T-shirts every day of junior year. Ben wanted to become a missionary in Africa and live off of nothing. When enrollment opened for Bible camp every summer, he was first to apply, and that is where he met Kami when they were 14.

Some of their fondest memories took place at Lakeside Bible Camp, and decades later, Ben and Kami took their kids to the same place, plying new memories onto the old ones.

“Ben was into me before I was into him,” Kami says, laughing. She sits to Ben’s right on a bench in the dining room after refilling their coffee. “I thought you were a cool kid, but you zeroed in on me.”

“All the girls were tan and trendy,” Ben says, sipping his coffee. “Everyone had a Bath & Body Works scent. What they wore, what they thought was important, it all seemed dictated by large companies. But Kami …”

“I was tone-deaf to those things,” she says. “I didn’t really care.”

“She would wear jean cutoffs with a Gap T-shirt. You weren’t bubbly, which made me interested. I was more attracted to quiet …”

“Mysterious,” Kami interrupts, and they both laugh before Ben continues.

“I would write letters to her and she wouldn’t write back.”

None of it deterred Ben, even after Kami told him she would never marry him. She was honest, which he liked, and wanted more of in his life. On Christmas in 1999, Ben proposed holding the engagement ring he bought for $229. He told her he wanted to follow Jesus for the rest of his life, and he wanted to do it with her. At the time he was interning at a church, helping with the youth and college groups. He still dreamt of becoming a missionary and believed that he had found the perfect partner in Kami, who was both gentle and kind. Crouched on one knee, Ben told Kami their life was going to be hard.

She said yes, and they married one month later, two 20-year-old kids. They lived in a one-bedroom student apartment, relied on food vouchers and push-started their Hyundai down a hill every morning. Kami was two years away from completing her nursing degree, which they believed would be valuable in their life as missionaries. Ben had dropped out of Multnomah University in Portland, quit a construction job he hated, and then found a job he loved, working at Red Robin for $17 an hour and free fries.

Dove was born a year after they married.

“Family life is all we’ve known,” Ben says. Friends and family members liked to heckle him, saying his life was over — “see you in 18 years” — and Ben watched as his friends shed their old lives for new ones as parents, which seemed to be defined by love, but also self-sacrifice.

“That never felt right to me,” he says. “There was something fishy about the way that parenting was done — change everything, put the kid in the center. We said f— it, we’re going to live our life and do the stuff that we think is interesting and we’re going to bring our kids along with us.”

When Kami was pregnant with their second child, Eden, Ben proposed a three-month cross-country bike trip. He quit his job at Red Robin, bought two Trek mountain bikes and outfitted them with road tires that would take them some 3,200 miles, from Virginia Beach to Seattle. Baby Dove rode in a trailer with a little red flag that hitched to Ben’s bike and off they went.

“We didn’t know what we were doing or anything,” Ben says. He tells me a story. Miles of rich open farmland stretched in front of them. A storm brewed overhead. “We had never seen rain like this,” he says. Ben, Kami and Dove raced across a field and hunkered down in a barn. Lightning blazed across a churning sky and painted the landscape with streaks of light. They were soaked to the bone and chilled, but safe, and witnessing something beautiful together. “I’ll never forget it,” Ben says.

They made it to Damascus, Virginia, and slept in a good Samaritan’s garage on bales of hay with Appalachian Trail hikers. The next day, they got back on their bikes and pedaled west. A car smashed into them some 100 miles later. They never saw it coming. They were cycling and then they were on the ground, bike wheels still spinning.

“We could’ve died for sure,” Ben says. “But we didn’t.”

They were injured and stranded with a 1-year-old in the Appalachian Mountains without IDs, money or their belongings, which had been left on the road when the ambulance came. The worst had happened and they were OK, forged by an experience they had shared together. Years later, Ben and Kami, scars on her back from the crash, returned to Damascus while thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail with their six kids. “This is where it all started,” they told the children.

After the bike crash, the family returned home, but Ben no longer had a job and was wondering what to do next. Before the bike trip, he had bought a book — “How to Make $100,000 a Year Gambling for a Living” — and thought little of it beyond it being an interesting read. The bike trip unlocked a new way of thinking, a “mental freedom,” Ben says, that made him reconsider how a chapter about card counting might change their lives. He asked Kami if she trusted him, and after her blessing, took $800 — the last of their savings — to a casino. He tucked a credit card-sized piece of paper with card-counting strategies into his pocket.

His $800 grew to $2,000 in one night. Ben started playing with two friends, then three, which became a small team when word spread. “The bike trip, taking that risk of going against social norms, created this confidence for me to take other risks, Blackjack being one of them,” he says.

Starting in 2006, Ben co-managed a Blackjack team made up of mostly devout Christians. They called themselves the Church Team, and leaned into the novelty of card-counting Christians traveling to casinos across the country. NPR and the New York Times did stories on them, and they were the subject of a documentary, “Holy Rollers: The True Story of Card Counting Christians.”

“It was a team of predominantly Christians,” Ben says. “It was double weird.”

Card counting isn’t illegal, but casinos ask suspected card counters to leave. Sometimes Ben and his teammates dressed in disguises. There are pictures of Ben dressed in goth garb complete with eyeliner and painted black nails, one of him wearing a white turban with a fully grown beard, another photo of him dressed as a geek from MIT.

By the time the Church Team disbanded in 2011, Ben says he had begun to burn out. Playing Blackjack had fundamentally changed the way he saw money, and he was no longer interested in making it. He had bought a house with the money he made from casinos, but felt lulled into the trap of needing to make more, to fill their nice house with nice things for his kids, which felt like the dream of every parent and, for a while, his own. But it would never be enough.

“The bike trip, seeing that we could be happy on $10 a day, I was always like, if Blackjack doesn’t work, I can work at Wendy’s and have a happy life,” Ben says. “I could get paid $5 or $10 an hour and I can do s— with my kids. The things that are most important for me with my kids, you can’t buy.”

A FEW HOURS before dinner, Rainier sits at a table pushed up against the dining-room wall. An abandoned throw blanket pools underneath on the wooden floor. He swivels in his chair, legs scrunched up against his chest, and pulls up a YouTube clip from 2016 on the family desktop. His birth video — “New BABY! Home Birth with Family” — fills the screen and begins to play.

Kami peers at the computer and smiles. “Ah,” she says. “That’s a classic. It’s kind of intense.” The three of us watch as the video version of Kami squats inside an inflatable pool and breathes through a contraction. A midwife hovers nearby and offers encouragement while each of the Crawford daughters take turns holding Mom’s hand, brushing her hair back. Ben sits in the water with Kami. “The head’s right there,” he says, and Kami begins to push.

I sit on a bench and watch Rainier watch himself. “Mom?” Rainier asks. “Can I have a bowl of cereal?”

All of the Crawford kids were born at home or at a birthing center, a decision Kami and Ben made so they could be surrounded by family and friends. As Rainier took his first breath, Dove and Eden cried. Kami tucked baby Rainier into the space between her head and shoulder, right over her heart. “I love you,” she said. “I love you.” Seven cut the umbilical cord.

Birth, the Crawfords believed, was a gift from God, and meant to be shared, and so making a video and posting it for the world to see was an easy decision. It became, and still is, the most popular video on their YouTube channel, with 3.8 million views. It validated for Ben and Kami not only the need to reclaim the beauty of birth away from a clinical setting, but the feeling that we as a society, as families, are starved for this type of intimacy.

For years, starting in 2015, the Crawfords vlogged nearly every day — 10- to 20-minute clips of their daily life uploaded to YouTube. Ben named the channel “Fight for Together,” and in the early days of the vlog, he devoted hours learning how to edit. They started vlogging because they wanted to show what family life could look like when it wasn’t dominated by year-round sports, overnight summer camps, carpool schedules and school. (All of their kids were homeschooled at the time.) The vlog was also, Ben and Kami say, modern-day missionary work.

Ben posted the mundane. Coffee in the mornings and family meals, teenagers squabbling and making up, birthdays and holidays. He posted the outlandish, videos with titles designed to entice. “Our Worst Parenting Fears” and “Married Vloggers Fight.” “I crashed my parents mercedes” is another popular one. When people commented, asking about Ben’s former career as a professional Blackjack player, he made several videos about that too — “A Day in the Life of a Retired Blackjack Player,” and “FINALLY Back in a CASINO.”

Rainier likes to watch old videos, and quotes lines from his favorite ones like an old and familiar movie. There are hundreds of videos on their channel, documenting nearly a decade of family change.

In an early vlog from 2016, with the camera propped up on the table of a coffee shop, Ben explains that families were designed by God as a way to better understand God himself. “We wanted to show our life and let it speak for itself,” Kami says in the video sitting across the table from Ben.

That was when life was good. Really good. Ben and Kami were valued members of a home church led by Kami’s brother, Jeremy Pryor. Their family friends — many of them part of the same religious community — lived within a 3-mile radius. Some lived just a few doors down, renting properties owned by Ben and Kami. Friday nights meant shabbat dinners and communion at the Crawfords’ house. Birthday parties drew 30 or more guests. They hosted Bible readings for kids and adults. New husbands and new dads asked Ben if he would mentor them, and he took special pride in the requests. Epipheo, an internet startup that Ben had cofounded in 2009 with Pryor and two other Christian friends, was growing and creating explanatory videos for clients like Microsoft and Google.

Every morning Ben opened his Bible and saw in it validation of everything they had built, a manifestation of the life they had envisioned years ago when Ben proposed to Kami and said he wanted to follow Jesus, and he wanted to do it with Kami by his side.

He had always gravitated towards extremes. Ben could be obsessive almost about the things he felt drawn toward, and religion was the sun around which all other things orbited. In college, Ben and Kami agreed to take a break from dating because Ben worried he had begun to love Kami more than God. “One thing that’s absolutely true about Ben is that when he puts his mind to something, he can go after it,” says Mark Treas, a former Church Team member.

Vlogging about their life, the one that he and Kami had created together, became Ben’s new passion and obsession. It was about to unravel the very life he meant to share.

THIS PAST OCTOBER, Ben flew to Houston by himself to get his 16th tattoo. He got his first — a fish, to symbolize his Christian faith — on the day he turned 18. They represent to him who he was and what he believed at each juncture of life. His newest tattoo took seven hours to complete and covers his neck from his Adam’s apple to collarbone. “Man, it hurt,” he says. Boxes and straight lines form the edges of the tattoo and merge toward the center into a mandala drawn with softer lines and curves.

“It’s kind of a visualization of what it was like for me to transition from rigid, boxy, religious beliefs to more fluid, spacious and rounded beliefs,” he says.

Ben and Kami have spent years examining painful questions about the events that spiraled over a two-year span and left them separated from their church and faith community by 2018. One day, Ben says, Pryor gave him a multipage document containing Bible verses accusing him of pride, which then led to a spiritual discipline process. He was required to meet regularly with his mentor, and told to stop vlogging for a week. He spent his days upstairs in the family attic reading the Bible from morning until evening.

He also was ordered to see a therapist. He didn’t want to go, and picked the most expensive therapist hoping they would also be the most qualified to fix whatever was wrong with him as quickly as possible. But after an early session, Ben called Kami from the car. She could hear him crying. Maybe, he said, he wasn’t a monster. Maybe the problem wasn’t him or their family, but the religious community they were a part of. “Therapy was our saving grace,” Ben says now. “It actually saved our ass.” Eventually, Ben and Kami started going to therapy together. Having an outside perspective felt empowering, and those sessions set in motion realizations that made staying in their religious community impossible. They had become different people.

“Growing up in religion, spirituality looked very boxed-in and narrow,” Kami says. “Five or six years ago, that box just sort of blew open and it was like, ‘Oh, there’s a whole other world out here.'”

“We were basically in a cult,” Ben says.

Ben says now that he believes they were kicked out of the church in part because of the vlog, that the foundation of their community was based on submission to authority and the vlog epitomized the lack of control religious leaders had over Ben and Kami’s ability to share their own story.

The shabbat dinners, Bible studies and weekly gatherings all came to a stop. Ben says he ran into a good friend at the coffee shop only for the friend to say he wasn’t allowed to speak to him. Their friends moved out of the houses they had rented from Ben and Kami. Ben sold his shares in Epipheo and the Blackjack website he had started with his Church Team co-founder. Over email, Pryor asked his sister Kami not to contact him anymore.

“We were shunned, but we played a part in that too that I don’t regret,” Ben says. “We were kicked out, but also we didn’t comply. If I would’ve known…”

He pauses. Starts again.

“If I would’ve known, I don’t know if I would’ve complied or not. It’s hard.”

Two years after Ben’s meeting with Pryor, the Crawfords’ trip to the Appalachian Trail felt less like the family adventure they had planned than a time to heal and walk off a version of their past selves. It was an opportunity to reexamine everything they knew and believed, especially when it came to parenting. For years, the family had a set of rules written on the chalkboard wall in the dining room: “Work Hard.” “Crawfords Never Quit.” “Submit to Authority.”

I ask him to repeat the last rule — submit to authority. “You literally had that written down?”

“Oh yeah.”

“We viewed our job as parents to make sure our kids turned out OK, which basically involved a lot of rules. We felt like our job, as religious people, was to follow the rules.”

They had rules about showers — the kids were expected to shower once a day, for 10 minutes max, and every minute past meant paying 10 cents. Laundry days were assigned to each of the older kids, and it needed to be finished by 4 p.m. or else they had to pay $1 for every hour past, plus an extra $10 if they forgot entirely. Posted on the fridge, Ben and Kami maintained a chore chart and family schedule that mandated quiet time from 8:30 to 9 a.m. But the biggest rule of all was listening to Mom and Dad.

“Rules were the basis of our relationships,” Ben says. “They had become more important than other things.”

After returning from the Appalachian Trail, they did away with rules entirely for a year. When the kids wanted candy, they were allowed to have it. Bedtimes and screen time limitations were no longer enforced. Homeschooling, too, began to look different. Instead of a traditional curriculum focusing on science, math and reading, the kids followed their passions. Memory, for example, attended pottery lessons taught by a family friend. The kids were entrusted to decide when to go to bed, when to wake up, what they wanted to do with their days and what they wanted to learn.

The older kids talk about a “before” and “after” — there’s a clear distinction between the way they were brought up and how Filia and Rainier are raised today.

“I think they broke this cycle,” Memory says. “How they’re parenting us currently, it’s not how they were parented.”

“They just stopped believing that it was their job to direct us what to do,” Dove says.

The metaphor Ben uses to describe his ideal parent-child relationship is like having a boss you can drink a beer with. (Ben says he doesn’t care if his kids drink underage so long as they also understand the legal consequences.) Sometimes the boss has to make hard calls — “I’m not anti-rules, if my kid’s crossing the street and there’s a car I’m going to do everything I can to knock him down,” he says — but it’s mostly an equal partnership.

“Getting kicked out of our whole community and family, we started to shift our priority as parents from enforcing rules to just radically accepting whoever they are and listening to what they said, listening to who they are and what they want instead of shoving what we thought was right down their throat,” Ben says.

He is most proud of his kids’ abilities to express themselves, that they feel safe enough to do so. Dove is a photographer. Eden paints murals. Seven creates videos. Memory plays piano. When I visited last March, Filia showed me her drawings and her handsewn animals made of felt. Ben says his kids have a voice that he never had, and he feels like he is making up for lost time. It’s why he’s so passionate about his writing. He’s published four books in two years. He’s working on one now, about parenting.

When I leave the Crawford’s house later that afternoon, Kami is in the living room picking at a guitar. In 2021, she released her first album and has released two more since. The room next to Ben’s office has been fashioned into a recording studio of sorts. Her voice is feathery when she starts to sing.

Some people won’t sail the sea ’cause they’re safer on land / To follow what’s written / But I’d follow you to the great unknown.

ON THE DAY of the Flying Pig Marathon in May 2022, Ben posted a picture of the family at the starting line on Instagram. He posted again midrace — a selfie with Kami and Rainier. A day later, he posted a photo of Rainier at the grocery store holding the Pringles he had been promised at mile 20.

“He was struggling physically and wanted to take a break and sit every three minutes,” Ben wrote in the caption. “After 7 hours, we finally got to mile 20 and only to find an abandoned table and empty boxes. He was crying and we were moving slow so I told him I’d buy him two sleeves if he kept moving.”

The comments trickled in.

“Appalling child abuse. You should be ashamed of yourselves.”

“This isn’t a lesson in resilience. It’s a lesson in manipulation and it’s gross.”

“6 year olds do not need to be running marathons …. ever heard of T-ball?”

Then they swelled into a flood when Kara Goucher, an Olympic distance runner, tweeted. “A six year old cannot fathom what a marathon will do to them physically. A six year old does not understand what embracing misery is. A six year old who is ‘struggling physically’ does not realize they have the right to stop and should.”

“It became a total s— storm,” Goucher says. It got ugly on both sides. Suddenly people were commenting on posts of Goucher’s son to criticize her own parenting. She says she blocked more people after tweeting about the Crawfords than she had in her entire career. “I wasn’t trying to judge, I was just trying to say, ‘I don’t think this is a good idea,'” Goucher says.

Ben refused to concede any ground to critics. In the week after the marathon, the Crawfords appeared on “Good Morning America.” Six days later, Ben told Piers Morgan in an interview that he believed his role as a dad was to show his children that anything was possible. When Morgan said at the end of the segment that Ben may have changed his mind, Ben gave a soft smile. The family also wrote statements on Instagram addressing what they call a wave of misinformation, compiled a four-page FAQ for anyone interested, and wrote an open letter that included subheads titled “Science and Medicine,” and “Parenting in Peril.” One section, under the subhead “Freedom and Health for All,” draws a connection between the decades-long bans against women in distance events to the ones today against children like Rainier.

“Ben just doesn’t do things in the way other people do,” says Ford Knowlton, a former Church Team member. “I think part of it is that he doesn’t want to. I sometimes make decisions to live differently than other people or change the way I’m living and I just do it quietly, but he loves to put it out there and cause tension and friction. I think he likes to help people wrestle with what they believe or how they live. He likes being a challenger.”

Still, the critics kept coming. Eden googled her family every day out of morbid curiosity. One national headline read, “Parents receive backlash for allowing 6-year-old to run a marathon.” Another, “Flying Pig Marathon: Controversy as six-year-old boy takes part.”

“It didn’t feel like they were describing us,” Eden says. “It felt like it was just another news article that happened to have the names of people that I knew.” Some of the comments on the family’s social media accounts spilled over into her personal account. The messages ranged from pity — “poor kids” — to accusing her of being brainwashed by her parents. “It felt really disempowering. What do you say to someone like that?”

Dove says someone egged their house, hitting Memory’s window upstairs. The worst was when Child Protective Services arrived. Someone had called saying they saw Ben and Kami drag Rainier along the course. The investigation found no evidence of abuse, but the events left Kami shaken.

“I knew they weren’t going to take away our kids, but they have the power to do that,” she says. “If you do anything out of the ordinary — which is really just out of the cultural norm — it can be really easily demonized.”

Kami told Ben she was afraid to run outside, and the family took three weeks off. Ben and Kami gathered the kids in the dining room and brainstormed things they could do instead of doomscrolling. Eden wrote the list on the chalkboard. “Go for a walk,” someone suggested.

“Call a friend.”

“Yoga.”

“Write a poem.”

Over the next few weeks, Ben and Seven worked on a documentary about the race. They wanted to show how Rainier encountered real struggles along the way but triumphed over each one. They also wanted to silence the family’s critics. Ben and Seven believed it would be one of the most important videos they would ever make. It played at a local theater and Ben posted it on YouTube in June 2022. Titled “Marathon Boy,” the 80-minute video has 1.1 million views and more than 2,600 comments — many of them positive.

“Kudos to the Crawfords for allowing their kids to be thinkers and doers. They’ll all be better adults because of their upbringing.”

“Rainier is a real life superhero.”

“All of what I saw here is what I aspire to be as a parent.”

The few medical studies on the long-term effects of distance running on children are inconclusive. The sample size is limited because children aren’t regularly completing marathons. “There’s no definitive, ‘this is good,’ or ‘this is bad,’ says James Smoliga, a professor in the Department of Rehabilitation Sciences in Seattle within Tufts University School of Medicine. “Every kid’s different. Every parent’s different. Of course they’re going to have different opinions, which is why it went viral.”

Many races, including the Flying Pig, offer shorter races for kids. The Flying Pig even holds a “Flying Piglet” for babies, a 15-foot crawl. Children over the age of 7 can participate in a mile race. Ben knows all of this, but isn’t interested in those options. He’s been running in the Flying Pig with his kids for a decade, since Seven was 8 years old. He didn’t know if they’d finish, but figured they’d try, and has been posting pictures and videos of his family running together on social media ever since. They wear uniforms — neon tank tops and red shorts with a letter C. The Crawfords aren’t trying to break records or send their kids to the Olympics — Rainier’s marathon time breaks down to a 19:41 mile pace — they’re running for fun.

Until 2022, no one seemed to care. But now that his youngest child had given him a platform, Ben was ready to use it.

RAINIER SEARCHES THROUGH his cubby in the dining room, hunting for the 2022 Flying Pig medal he earned 10 months earlier. He pulls out a T-Rex figurine missing its head, a duct tape wallet that Seven made, a Happy Meal toy from McDonald’s and a plastic Easter egg.

“S—!” he says. There’s a funky purple goo stuck to the bottom of the cubby. “How did this get in here?” The medal is somewhere in the back, and after passing it to me, Rainier goes about trying to separate his marathon race bib from the goo, which is pretty much superglued in place.

“Mom? Can you help?”

He’s small for his age, with freckles and long blond hair that drapes over blue eyes. He lost his two front teeth a few weeks ago, creating a thumb-spaced gap when he smiles or giggles, which happens a lot. Filia is nearby playing with the cat. A few minutes ago, Memory came down to ask Ben how to set up direct deposit for her new job at the Starbucks down the street.

Ben is sprawled on the living room couch reading a book when I ask for a house tour. “Sure,” he says. “Let me just finish this chapter.”

A few minutes later, we walk upstairs. A massive painting of a tree wraps around the stairwell, its branches stretching higher and higher until they curl around the ceiling, three stories up. “My brother did this mural,” Ben says. The leaves, painted in a lush green at the base, shift into golden shades of yellow towards the second floor. In Seven’s bedroom, there’s a mural of Mount Rainier that Eden painted. In Filia and Rainier’s room, Eden painted a forest landscape in hues of blue and green that spans the entirety of one wall. They once had six beds stacked in this bedroom. Now only three remain. Memory sleeps in the bedroom that Dove and Eden once shared.

“There’s a bit of Wild West vibes to the walls of the place,” Ben says. “I view the house as an art project, which has been an ongoing thing.”

We continue up to the attic. There’s just one window, and from it we can see the Crawfords’ backyard, which connects to the house of Ben’s parents. Ben points to his right and a house he and Kami bought in 2019. They gave it to their three oldest kids along with $45,000 to fix it up. “In lieu of college, my mindset was we’ll give you a house,” Ben says. “If you want to go to college you can sell it, or you can keep it, it’s kind of up to you.” Now Dove lives there with her boyfriend. Tucked between the main house and Dove’s, just out of view from the attic window, is a tiny home where Eden lives.

We pad back downstairs, the wooden steps creaking. Ben sits at the head of the dining table, alone. A balloon from somebody’s birthday idles by his feet and floats from one spot to the next. He’s lived in this house for more than a decade; Rainier was born in it, his kids were raised in it. Despite all the outside noise stirred up by Rainier’s marathon, Ben remains confident that he and Kami have done it right. A few months from now, Eden will move out of the family compound and into an apartment two miles away to start community college.

“Togetherness in our family looks different than it did eight years ago,” Kami says later. “It’s supposed to. All of our kids are in a different place and they have different needs. So do Ben and I.”

Ben and Kami raised their kids to believe in their autonomy. They know their kids can use those very lessons to one day leave and forge their own paths, the way Ben and Kami did when they created new lives outside of religion.

Ben wants his kids to know independence and freedom, to be able to run marathons and know that their legs are capable of carrying them 26.2 miles and beyond, to wherever they wish to go. He hopes that he and Kami have built the type of home that their kids will want to return to. Sitting at the distressed table, he faces the chalkboard wall where Kami used to write down the kids’ schedules. Now she writes plans for Filia and Rainier only — the older kids no longer need it.

“If my kid looks at me in 20 years and says, ‘You ruined my life,’ what am I going to say?” Ben says. “I don’t want to ruin my kid’s life.”

IT’S EARLY MAY 2023, about a week after Rainer finished his second Flying Pig Marathon. He peers into Ben’s phone, the screen pulled up to my FaceTime call. He swivels his tiny body in his dad’s office chair and sits cross-legged, his thumb popped into his mouth.

“Hiiii,” he says.

“Can you take your fingers out of your mouth so she can hear you?” Ben asks.

Kami and Ben spent weeks before the race fretting over what would happen if Rainier was spotted running, if he would be hassled or pulled off the course by race officials. In 2022, Rainier was allowed to register. Now, organizers said he was too young to run. Online, Ben said he wouldn’t engage with “haters,” but he reposted screenshots of the previous year’s tweets from Goucher and another Olympic runner. “Who I would trust to raise my children if I died, in order of preference,” he wrote, followed by:

1. Homeless Drunk

2. Pro Wrestler

3. Catholic Priest

4. Olympic Athlete

“Ben … I think he takes the social media thing a little too far,” Harvey Lewis says. He’s a professional ultra-runner and a Cincinnati local who’s run in every Flying Pig Marathon since it started in 1999. “Maybe he’s trying to change people’s perceptions, but I feel like there’s a cost to that.”

Lewis knows the family and likes the kids a lot. Eden recently reached out for advice on running an ultra-marathon. A high school history teacher, Lewis doesn’t want to say anything that would hurt the kids. He recognizes the hypocrisy of what he’s about to say — he was 15 when his mom signed him up for his first marathon, an experience that changed his life — but letting a 6-year-old run 26.2 miles seems extreme. He points out that Ben and Kami gave Rainier Children’s Tylenol midrace, a clear indicator to him that the distance is too much.

“Is it OK to just let your child sail around the world when they’re 6 or 7 years old?” Lewis asks. “Where’s that limit ever drawn?”

Rain poured the day of the 2023 Flying Pig. It made it hard to see, and Rainier held on tightly to Ben’s hand as his dad guided him through flooded streets. Kami decided not to run, but she met up with Rainier and Ben at various spots throughout the course. So many people gave Rainier midrace high-fives that Ben told Rainier he didn’t need to acknowledge every one if the effort was wearing him out. Ben and Kami’s worst fears never came to pass.

“I didn’t want to quit,” Rainier tells me now over FaceTime.

“Why not?” I ask.

“I like doing stuff with my family.”

Rainier repeats this a lot when you ask why he runs. “Our family does hard things.” Or, “This is what we do.” It doesn’t seem to occur to him that none of his friends are running marathons. But they were there to cheer him on at mile 24, his favorite part. At mile 25, he says, they were going “really fast.” His grandma, aunt and cousins waited along the course with raspberries, grapes and watermelon. He stopped at every playground he saw, took breaks when he wanted, and then crossed the finish line in 8 hours and 15 minutes, 20 minutes faster than his time when he was 6.

“I want to run at least five marathons,” Rainier says. “So far I’ve done two. I think I’m going to do at least three more. But it kind of depends if my dad wants to do it. If my dad doesn’t want to do it…”

He pauses.

“I won’t do it.”

It’s 3 in the afternoon. He’s supposed to go on a training run with Ben. They have plans for a four-mile run, maybe five. Later he has a playdate with one of his best friends. Dinner is in a few hours.

And after that, he tells me eagerly, he’s been promised computer time from 8 to 9 p.m.

It’s his favorite part of the day.

You may like

-

PCB advertises for Red Ball High-Performance Coach

-

Is continuity enough to get the Bucks back into title contention?

-

Will Sauce Gardner’s quest to be the best CB be overshadowed by lack of interceptions?

-

Revised schedule of Pakistan vs England Test series announced

-

ICC delegation satisfied over Champions Trophy 2025 preparations

-

South Africa inflict 2-1 defeat over Pakistan in women’s T20I series

-

Sources: ACC, Clemson, FSU renew revenue talks

Sports

PCB advertises for Red Ball High-Performance Coach

Published

3 گھنٹے agoon

ستمبر 21, 2024By

l955w

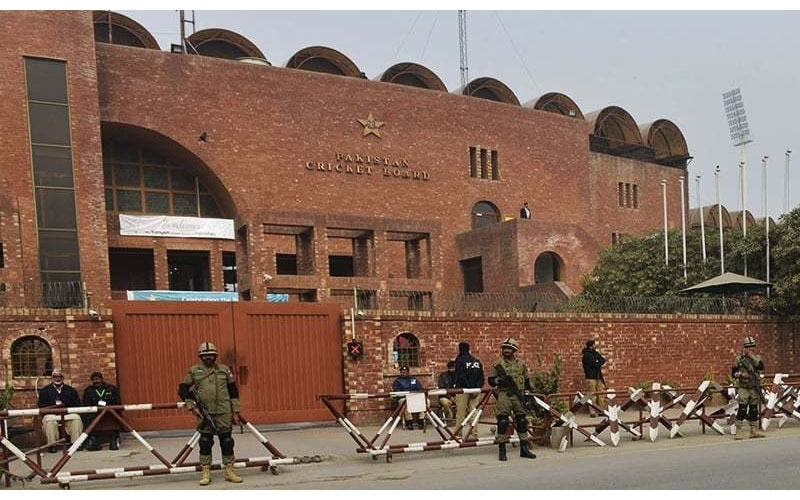

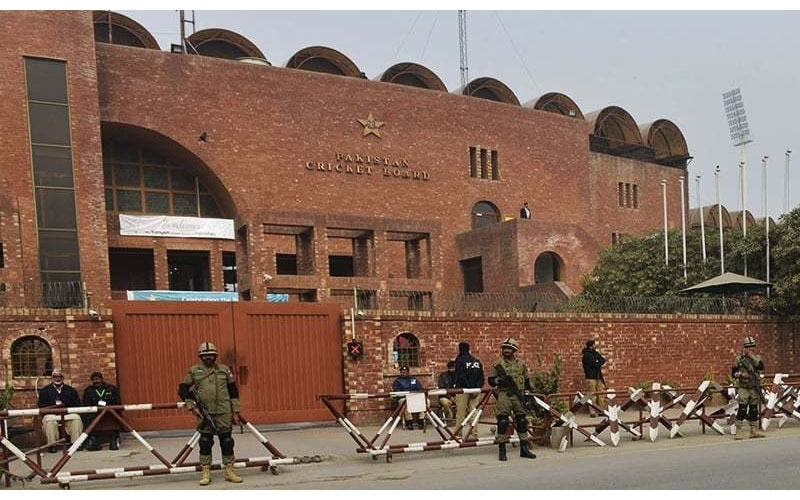

Lahore: Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) issued an advertisement to search for a High-Performance Coach for the Red Ball Team.

The High-Performance Coach will assist the Head Coach in game planning while he will also work closely with the Head Coach in pre- and post-tournament preparations to enhance performance.

As per PCB, five years’ experience and minimum level two coaches are eligible to apply, aspirants can submit applications till October 7.

In the series against Bangladesh, Tim Nelson took over as high-performance coach, brought in by Red Ball coach Jason Gillespie from South Australia.

It is also reported that Tim Nelson will be Red Ball’s high-performance coach, advertised as a necessary step for a permanent appointment.

Sports

Is continuity enough to get the Bucks back into title contention?

Published

9 گھنٹے agoon

ستمبر 21, 2024By

l955w

Trent had known Rivers since he was 6 years old thanks to his father, Gary Trent Sr., whose NBA career overlapped with Rivers’. Trent Jr. had been a productive player with the Toronto Raptors for three and a half seasons but failed to reach an extension or find a multiyear deal on the free agent market. Word was out that Trent could be seeking a one-year deal for the 2024-25 season, and Rivers jumped at the opportunity.

The Bucks were seeking a replacement in their starting lineup for guard Malik Beasley and saw a youthful energy in Trent, who could fit smoothly alongside Milwaukee’s superstar duo of Giannis Antetokounmpo and Damian Lillard.

Signing Trent to a one-year deal served as the biggest offseason addition for a team that prioritized depth signings over bold moves. The Bucks also swapped out players such as Jae Crowder and Patrick Beverley, who saw their roles and production reduced during the postseason, for a new crew of veteran backups in Delon Wright and Taurean Prince.

After a year of change and turnover for the Bucks — in the past 12 months they swapped Jrue Holiday for Lillard, and hired and fired coach Adrian Griffin before turning to Rivers midway through the season — a quiet summer was welcome for a team that enters the 2024-25 season trying to balance the benefits of continuity with the urgency of its championship expectations.

“We have that stability,” Antetokounmpo said the day after the team’s first-round playoff loss to the Indiana Pacers. “We’re not questioning and trying to figure out how it’s going to look moving forward.

“Now that you know, you just got to work.”

Bucks general manager Jon Horst was limited in his flexibility to change his roster this offseason. Milwaukee’s draft picks were depleted by the trade for Holiday in 2020 and for Lillard last year. Because of the restrictions of the new collective bargaining agreement, the Bucks did not have salary cap space and weren’t allowed to aggregate contracts, acquire a player via sign-and-trade or use the tax midlevel exception.

It left them with little options aside from adding players via the veterans minimum.

Besides, it had still been less than a year since Milwaukee swooped in for Lillard before training camp, sending a package to the Portland Trail Blazers that included Holiday — the starting point guard on the Bucks’ 2021 championship team — who was then sent to the eventual champion Boston Celtics. It was a bold move that paired an All-NBA guard in Lillard with a two-time MVP in Antetokounmpo, with each being the most accomplished teammate either player had ever played with.

Lillard’s arrival also paid off in another way, as Antetokounmpo committed to the Bucks by signing a three-year, $186 million max extension that begins this season.

Antetokounmpo inked his deal one day before the start of the season, but the Bucks’ positive momentum didn’t carry into the games.

Lillard was slow to adjust to a new environment and struggled to find on-court chemistry with Antetokounmpo. Griffin was fired 43 games into the season (with a 30-13 record) before the team turned to Rivers, who went 17-19. With Antetokounmpo missing the entire six-game series against the Pacers because of a strained left calf and Lillard limited by an Achilles injury, the Bucks crashed out in the first round of the playoffs for a second straight season.

When Rivers took over the team in February, he acknowledged how difficult it would be to turn a team around midseason. Now with a full offseason and training camp, he will have an opportunity to establish a style of play, including by adding role players who better fit his vision.

“Think about it: Giannis worked out all [last] summer not knowing he was going to have Dame,” Rivers said the day after last season’s playoff exit. “Dame worked out a little bit, not knowing he was going to have Giannis. Khris [Middleton], the same way. Now all three of them get to work out this summer knowing some of the things we’re going to do.

“The most important stuff is the sets and the stuff that you’re going to run, giving it to them long before camp starts. Because it’s easy for a star player to understand what he can do, it’s better when he understands how he can make everybody else better through those sets.”

The Bucks are betting on a full offseason and training camp to help build chemistry for Lillard and Antetokounmpo. Still, they were encouraged by the numbers with those two players on the floor last season: The team was plus-10.2 points per 100 possessions last season when their two stars shared the floor.

“I’m willing to put in work this summer. I think I have guys around me that they’re willing to do so,” Antetokounmpo said at the end of last season. “I saw how Dame was after the [playoffs]. I saw how Khris [Middleton] was after the game. … I know they’re going to put in the work.”

The question for Milwaukee is how the Bucks will compare to the rest of a stacked Eastern Conference.

Boston is coming off a historic season in which it won its league-leading 18th NBA championship. The Philadelphia 76ers just reloaded by adding superstar Paul George to play alongside Joel Embiid and emerging star Tyrese Maxey. The New York Knicks strengthened their core by adding Mikal Bridges. Emerging young teams, the Cleveland Cavaliers, Orlando Magic and Pacers, are on the rise, having finished with playoff spots last season.

Meanwhile, the Bucks return one of the oldest rosters in the NBA with four of their projected starters over 30. Antetokounmpo, who has been injured during the last two postseasons, turns 30 this season. Lillard will be 35 in October. Middleton is 34 and coming off offseason surgery on both ankles. Center Brook Lopez is 36.

“I always like a team that wins to have a little bit of experience, which comes from being a little bit older, knowing how to play the game and have that corporate knowledge of the game,” Antetokounmpo said at the end of last season. “And a little bit of energy.”

The age of its roster and the pressure to maximize each season of Antetokounmpo’s prime — “With Giannis, you’re always on the clock,” Horst told ESPN at the start of last season — guided Milwaukee’s bold moves over the past year in pursuit of another title.

Now the Bucks are counting on an offseason defined by continuity, a few additions to their depth and some better health during the postseason to give them a chance at another championship.

“We’re getting older. We’re not getting any younger, but that doesn’t mean we cannot still perform at a high level,” Antetokounmpo said. “It’s hard to say, ‘Yeah, we’re old and you have to make changes.’ Because these guys, they’re beasts.”

Sports

Will Sauce Gardner’s quest to be the best CB be overshadowed by lack of interceptions?

Published

10 گھنٹے agoon

ستمبر 21, 2024By

l955w

FLORHAM PARK, N.J. — Sauce Gardner doesn’t do vacations. The New York Jets cornerback doesn’t believe in them. The idea of chilling at a five-star resort, sipping fruity libations on a white-sand beach, doesn’t appeal to him. First of all, he doesn’t drink alcohol. No sauce for Sauce. Secondly, he’s a homebody. The Jets’ trip to London in two weeks to face the Minnesota Vikings will be his first time out of the country. He said he hasn’t taken a true vacation since entering the NFL in 2022, offering an existential reason. “Me, personally, I just feel like you’re just trying to escape the lifestyle that you live,” Gardner said in a quiet moment at his locker. “We play football, and we should be training. So going on that long vacation is getting away from what you’re supposed to be.” Which explains why he reported to the Jets’ facility two weeks after last season ended to begin training, three months ahead of the official start to the offseason program. It’s why his new, sprawling home in New Jersey includes a recovery room, complete with a red-light therapy bed, sauna, cold tub, treadmill and stationary bike. From the time he was 4 years old, playing flag football in the Tiny Mites league in the Seven Mile section of Detroit, Gardner’s singular focus has been to play in the NFL and be the best cornerback there ever was. A lot of kids dream that dream, but his early-career trajectory aligns with his life plan, and he’s just 24. Gardner is the only cornerback since the NFL-AFL merger in 1970 to be named first-team All-Pro in each of his first two seasons. Only three defensive players have pulled that off: former New York Giants legend Lawrence Taylor, Dallas Cowboys pass rusher Micah Parsons and Gardner, who said his individual goal this season is to be Defensive Player of the Year. Now if he could just get his hands on a pass or two, maybe that would silence critics who suggest the sauce isn’t as advertised. He will take a 26-game interception slump into Thursday night against the New England Patriots at MetLife Stadium (8:15 p.m. ET, Prime Video). Big deal or nah? LONG BEFORE HE shadowed wide receivers, Gardner shadowed his big brother, Allante. Despite a six-year age difference, the two were inseparable growing up. Even though there was an open room in their house, they decided to share the same bedroom. Allante played football, so Sauce played football, following him into backyard games against the big kids. When Allante changed his uniform to No. 2, Sauce switched to No. 2. When Allante worked out with a trainer during his college offseasons — he was a running back/wide receiver at Saginaw Valley State and Lakeland University — Sauce tagged along. “He was always right next to me,” said Allante, who knew there was something special about Sauce when he learned at the age of 5 to ride a bike with no training or training wheels. Gardner was always fearless, according to Allante, who said his kid brother once broke his arm doing a backflip off a fence. He said they both acquired their work ethic from their mother, Alisa, a single mom who worked two jobs to support them. If one of them wanted to attend a football camp, she worked overtime to pay the fees. Gardner said one memory of living at the corner of Rowe Street and Seven Mile East made an impact. When he was 14, he saw a man fatally shot outside a liquor store. Out of fear, he didn’t tell anyone. “It just made me come to the realization that you can’t take anything for granted,” Gardner said. “Me just witnessing that, I was like, ‘Dang.’ I just had to make sure I was locked in on everything — football, school, all that — because I knew ultimately where I wanted to go.” Whatever direction Gardner goes, Allante is there with him — even if it’s not physically. Allante, who still lives in Detroit, is a vice president at Vayner Sports — the company that represents his brother. Sounding like an agent, but speaking as a blood relative, Allante believes Gardner has the potential to be “a once-in-a-lifetime player.” Cornerbacks are often evaluated based on their interception total. That calculus can’t be applied to Gardner, who has as many Pro Bowls on his résumé as career picks (two). In an ESPN survey of nearly 80 NFL coaches, scouts and executives, one unnamed personnel evaluator called Gardner “one of the most overrated players in the league.” The same survey ranked him the third-best corner, behind the Denver Broncos’ Pat Surtain II and the Cleveland Browns’ Denzel Ward. Former star Richard Sherman, a three-time All-Pro cornerback, believes Gardner has benefitted from geography. “Obviously, being in the New York market helps,” Sherman, a Prime Video analyst, said on a conference call with reporters. “It helped [Darrelle] Revis, it helps Sauce. … He’s incredibly worthy [of his accolades]. He has been named first-team All-Pro. It’s not because he hasn’t played well, but it definitely helps playing in that New York market and getting that focus on you and then playing well while you’ve got that focus.” For his money, Sherman said Surtain is the best all-around corner in the sport, adding, “If he was in a big market, if he was playing for the Dallas Cowboys, I don’t think there would be any debate because people would be watching him all the time.” WHEN TOLD OF Sherman’s comments, Gardner shrugged. He agreed to a certain extent, saying he does profit from playing in New York. But he said that it’s a double-edged sword: More eyes on you means more pressure. Even Sherman acknowledged, “New York can chew you up and spit you out the same way it can raise your game.” Gardner added, “A lot of times, there’s no in-between.” Gardner welcomes the scrutiny. Asked if he’s the best corner, he said simply, “I try to do it as if I’m the best.” Former cornerback Jason McCourty, who played 13 years, had initial questions about Gardner despite his lofty draft pedigree — fourth overall in 2022. Those questions didn’t last long. “Even coming in, I’m wondering how he’s going to do it, covering these guys man-to-man, coming from [the University of] Cincinnati — and he’s just been awesome,” said McCourty, now an ESPN analyst, in a phone interview. “To step into the NFL and to be able to cover some of the best wide receivers, to be an All-Pro and to hit the ground running is just completely elite.” But what about the lack of interceptions? McCourty said it shouldn’t be a barometer, that Gardner’s ability to neutralize wide receivers trumps his low interception total. Sherman believes the game has changed. Gone are the days, he said, when corners such as Deion Sanders and Champ Bailey made the Pro Football Hall of Fame with gaudy interception totals — 53 and 52, respectively. In 2023, Revis, the former Jets star, was elected on the first ballot with 29. “I do think interceptions are important, but I guess, in this day and age, [people] don’t because there’s just not a lot of guys getting them,” said Sherman, who made 37 in his career. While the interception total may not be eye-popping, Gardner is a pass-breakup machine. His career total of 33 is the third most among corners since he entered the league. If he’s getting close enough to defend passes, in theory, he should be catching some of them. He knows this; he doesn’t shy away from it. Asked his goals for 2024, he said, “Get more picks and keep grinding for that Defensive Player of the Year [award].” He wants at least four or five interceptions. Gardner spends time after practice on every-day drills, including catching balls from a Jugs machine. His coaches love his work ethic. As cornerbacks coach Tony Oden likes to say, “Just when you think you’ve arrived as a player … bad things start to happen.” Whenever coach Robert Saleh is asked about ways in which Gardner can improve, he usually responds: Intercept the ball more often. Oden, always pushing his protégé, said “there’s more meat on the bone.” Perhaps, but his career is off to a historic start. He has pitched a league-high six shutouts since 2022 — games in which he allowed zero receptions as the nearest defender with a minimum of 20 coverage snaps, according to NFL Next Gen Stats. Gardner received the All-Pro nod with a zero-interception performance last season. For a corner, that hadn’t occurred since 2010, when Revis and Nnamdi Asomugha both did it. Uncommonly tall for a corner at 6-foot-3, with 33½-inch arms, Gardner makes it difficult for receivers to escape his clutches. His size and physicality allow him to jam bigger receivers at the line of scrimmage, according to McCourty. What really impresses McCourty is how Gardner can stick to smaller, quicker receivers at the top of their routes. These skills, he believes, could make him one of the best corners of this era. “When you have a longer guy, a taller guy that can run, it’s kind of tough for a receiver,” Tennessee Titans receiver Tyler Boyd said. “It’s tough to just run away from the guy, knowing how long and athletic he is. But don’t get me wrong, he’s beatable. Every DB in this league is beatable.” The Titans proved that Sunday, beating Gardner on a 40-yard touchdown pass to Calvin Ridley. The coverage was tight, but quarterback Will Levis dropped the pass between Gardner and safety Chuck Clark. All told, Gardner allowed five catches for 97 yards when targeted, his most yards allowed as the nearest defender in his career, according to NFL Next Gen Stats. It was an uncharacteristic day for Gardner, who rarely surrenders chunk plays. Afterward, in the locker room, he was shaking his head. “I still don’t know how he caught that,” he said. IN THE SEASON-OPENING loss to the San Francisco 49ers, Gardner recognized a gadget play was coming. On a third-and-5 from the Jets’ 29, he alerted teammates to watch for a reverse. Linebacker C.J. Mosley heard him before the snap, adjusted and helped trap wide receiver Deebo Samuel in the backfield. Mosley credited Gardner, calling him one of the smartest players on defense. “He’s become a real student of the game,” Mosley said. “He’s a lot more vocal than he was as a rookie.” Gardner made the tackle and was credited with his first career sack because of Samuel’s intention to throw a pass. “He’s a film junkie,” Allante said. Allante said Gardner watches about an hour of game film every night in his home theater, learning opponents’ tendencies and critiquing his own performance. He described it as a singular focus, saying his brother possessed it at an early age. “He’s a different guy,” Allante said. “He don’t drink, he don’t smoke, he don’t party.” Outside of football, Gardner plays video games — he’s an accomplished gamer — and hones his golf swing in his home simulator. Golf is a new passion. He proudly declares that he broke 90 for the first time before training camp. Life is good for Gardner. Business is booming. The price for Gardner will increase in the coming years, perhaps next year, when he’s eligible for a contract extension. The ceiling on the cornerback market was raised recently, when Jalen Ramsey ($24.1 million per year) and Surtain ($24 million) signed extensions. With another good year, Gardner could leapfrog both to become the highest-paid corner. Gardner received a phone alert when Ramsey’s deal was completed, saying his first thought was: “Dang, Pat wasn’t even the highest-paid corner for a day.” He applauded the contracts, noting that corners finally are closing the gap with the highest-paid receivers, but said he’s not looking ahead to his potential blockbuster deal. Gardner’s job as a corner is to make those receivers seem invisible. He’s also had a knack for making quarterbacks shy away from him. In two games, he has been targeted only eight times as the nearest defender, having allowed five receptions for 97 yards. In the offseason, he asked the coaches to give him the added responsibility of covering the opponents’ No. 1 receiver. Philosophically, the Jets’ staff is opposed to doing that on an every-down basis, citing scheme and personnel considerations, but they’re giving him a taste of it. In the opener, Gardner traveled with Brandon Aiyuk for a handful of plays and allowed no catches. In Week 2, despite the long touchdown to Ridley, Gardner was given a huge responsibility with the game on the line. In the final minute, with the Titans in the red zone, down by a touchdown, Gardner shadowed DeAndre Hopkins on four straight pass plays. Levis avoided that matchup. The result: Three incomplete passes, a sack and a 24-17 victory for the Jets (1-1). “We have a special talent in No. 1,” defensive coordinator Jeff Ulbrich said, “and Sauce can do some things that are so unique and special.” Gardner welcomes the challenge. He doesn’t mind playing on an island, the same way Revis did back in the day. Given his dislike for vacations, it might be the only island he enjoys.

Sports

Revised schedule of Pakistan vs England Test series announced

Published

20 گھنٹے agoon

ستمبر 20, 2024By

l955w

KARACHI: Pakistan’s cricket board on Friday announced a revised schedule for a series it will hold against England next month, ending weeks of uncertainty including reports it could be moved abroad.

The first two Tests will be held back-to-back in Multan and the last in Rawalpindi, skipping Karachi where ongoing construction at the National Stadium has forced the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) to tweak the schedule.

“The series will start in Multan with the first Test from October 7-11 and the second Test — originally scheduled for Karachi — has been shifted to Multan, as the stadium in Karachi is undergoing (a) major facelift for next year’s Champions Trophy,” said a statement from the PCB.

The second Test will start from October 15, while the third in Rawalpindi will be staged from October 24.

The England men’s cricket team will arrive in Multan on October 2 for their second tour of Pakistan in two years.

The announcement ended weeks of frustrating wait by the England and Wales Cricket Board who were seeking clarity on the schedule.

Moreover, there were media reports of shifting the series to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) where Pakistan was forced to play its home matches from 2010 to 2019.

Revised schedule:

7-11 Oct – First Test, Multan

15-19 Oct – Second Test, Multan 2

4-28 Oct – Third Test, Rawalpindi

Prince Harry’s ex-girlfriend makes sad admission about heartbreak

Dylan O’Brien recalls cringeworthy ‘Frozen 2’ audition experience

Prince Harry reclaims spotlight from Prince William with power move

Samsung’s new midrange Galaxy A55 has improved security, features | The Express Tribune

New Zealand in efforts to fast track consenting of major projects – Pakistan Observer

PCB opens applications for specialized red and white-ball coaches

Trending

-

Technology6 مہینے ago

Technology6 مہینے agoSamsung’s new midrange Galaxy A55 has improved security, features | The Express Tribune

-

Pakistan7 مہینے ago

Pakistan7 مہینے agoNew Zealand in efforts to fast track consenting of major projects – Pakistan Observer

-

Sports6 مہینے ago

Sports6 مہینے agoPCB opens applications for specialized red and white-ball coaches

-

Pakistan6 مہینے ago

Pakistan6 مہینے agoLegal issues hinder projects’ transfer | The Express Tribune

-

Entertainment6 مہینے ago

Entertainment6 مہینے agoPrince William foils Prince Harry’s reunion plans ahead of UK return

-

Sports5 مہینے ago

Sports5 مہینے agoConversation continues between PCB, New Zealand for white ball series

-

Pakistan7 مہینے ago

Pakistan7 مہینے agoNADRA NICOP fee March 2024 – Pakistan Observer

-

Pakistan6 مہینے ago

Pakistan6 مہینے agoExperts call for regulation of ChatGPT in education | The Express Tribune